In which I meet a man at a Pulp show who has done something unspeakable

of which he speaks

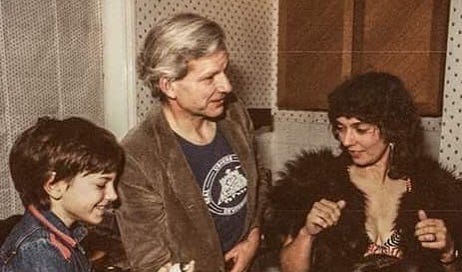

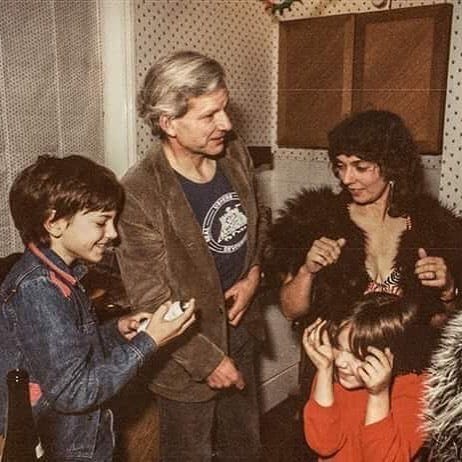

The Heawoods enjoying the 1980s.

My life was 92% future at this point.

I went to see Pulp the other day, at a big outdoor stage in London, with two friends. I soon bumped into another friend, and then while I was talking to her she bumped into one of her friends, and that guy, who I had never met before in my life, was - well.

The band hadn’t started playing yet so we were all milling around in late afternoon anticipation, queuing for frozen margaritas that were significantly more frozen than margarita, bumping into shadows from our pasts. Everybody was there, all the people we had ever sung along with at indie discos in scuzzy basements; venues that have since been turned into luxury developments, with windows the size of glory holes, for people who don’t exist.

(In my head, London is still the place I have moved to, not the place where I have now spent the majority of my life and in which I used to be young. It takes some getting used to, middle-age, with all of this remembering, all of these ghosts.)

This friend of my friend seemed smiley, bobbing about with a gaze that landed somewhere not quite on my eyes but near enough. He didn’t need to look at me anyway, he was talking to her; catching up with someone he clearly hadn’t seen for a while.

“You had a baby!” my friend said to him, having probably seen his life-changing news on a little photo on a little screen, pressed the heart button, and typed the word congrats. That thing that we are compelled to do, even if this friend is someone we met in a smoking area one random night seven years ago and who has played a relentless role in our internet ever since. Even if we care not, truly, for their lickle baby.

“Yeah,” he said, looking a bit over-energised, “yeah, yeah I took her, the baby yeah, I took her to the swimming pool today!”

“What, and just left her there?” I asked, forgetting this man was not familiar with my ideas around humour.

“No, no,” he started, looking at my face with some concern, or as close as he could get to my face, as close as he could get to concern, “my partner, my wife, she, we took her home, home, it’s…” He was sweating now; he was anxious, “cos my partner’s actually given me carte blanche to go for it tonight, stay out. I’m off the clock until Tuesday,” he continued, “so I’ve put two pills up my arse.”

I’ll be honest - that wasn’t where I was expecting a train of thought that began with a baby in a swimming pool to go. Carte blanche: not a red flag but a white card, meaning a blank document, which apparently allows you to insert two ecstasy tablets into your anus horribilis. Not wrapped in clingfilm to avoid security and bag searches outside the venue - oh no, he had popped them straight in there as a more immediate method of ingestion, a direct hit to the bloodstream.

And then he was off, the Pillsbury Arseboy, and I found my own friends and told them about him. One of them said she wanted go over to him and say “Hi, we just saw your wife, she said they found your baby at the swimming pool?” Or that we should get his phone number, wait til he was really coming up on those pingers and then give him a ring just as he’s gurning along to Jarvis at the top of his voice and interrupt him with, “Good evening, Sir, just a courtesy call from Better Leisure, we’ve got your baby here, you left it at the swimming pool?”

When I was fourteen I did work experience at a health food shop in my hometown, York. It had been set up by a group of friends in the 1970s and there was a framed black and white photo of them hanging above the till. Men with very long hair, flared jeans, beards, morals, dreams. I was standing beside one of them once, and as I stared at this old photo I asked if he wasn't embarrassed to have it there. He looked at me reproachfully. “We don’t all have more future than past to look forward to, you know.”

That comment of his is older now than the photo was then, but at the time I was startled. Amused. I also felt he should put up more of a fight with his language: it sounded, to me, like defeat.

- - -

And so Pulp performed ‘Babies’, strangely without mentioning whether any of them had been left in a leisure centre. ‘Sorted for Es and Whizz’ passed similarly without incident - they could have changed it to Sorted for Es and Shits, at least?

But oh god it was golden. It was so completing. We felt so full! And I realised that we weren’t just nostalgic for the songs we sang in the 90s, but that these were songs that had been nostalgic at the time. Songs about being a kid hiding in someone’s sister’s wardrobe, songs about first lust, songs about going to art school, all sung by a grown man. We were singing along to stories about being children that we remembered from when we were adults who were young. Pulp had always been a project of remembering.

I wondered if Arseboy was nostalgic too, for a time when he didn’t have a baby, or a wife, or Saturday mornings spent in the chlorinated municipal baths, leaving things behind. What he had really left behind, of course, was not the baby, but his life before he had one. I wondered if he wanted that life back. I wondered if he wanted to obliterate the baby and shove the marriage up his arse too. Or was this just a somewhat male form of Botox, of not going gently into that good night. Was this weekend his anti-ageing regime?

The French call it nostalgie de la boue: nostalgia for the mud, the dirt, the low-life and depravity of old. Perhaps every new parent simply requires a Saturday-night-til-Tuesday to forget they have ever known the smell of chlorine.

I walked home afterwards, even though it took ages, because the traffic outside Finsbury Park was blocked solid and the transport was screwed, and I felt sober (because the drinks queues had been too long), and glad to know the way. The streets felt hot and happy and whole.

Usually I avoid the tours of former favourites - I can’t bear it somehow, it’s never right. Even when I went to see the Pixies, who I think wrote the greatest music of their generation - the next day I just felt weird that I’d gone. And I wasn’t going to dare try for the Blur gig that was coming up after Pulp, because the risk that they’d play Country House was simply too great.

But none of this happened with Pulp. It seemed a generous act to give us a reunion. Not just with them, or with one another, but with the people we used to be. (“I think we are well-advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be,” wrote Joan Didion, “whether we find them attractive company or not.”)

Pulp let us be proud of our old selves, handsome devils that we are, that we were, while also gently leading me to realise that I might just have tipped the scales and become someone with less future available than past. And I’d like to tell my younger self that, as long as I’m blessed with a bit more time here, it doesn’t feel like defeat. It actually feels a lot more like relief.

“In my head, London is still the place I have moved to, not the place where I have now spent the majority of my life and in which I used to be young. It takes some getting used to, middle-age, with all of this remembering, all of these ghosts.” - I’m absolutely with you in this! X

Arseboy forever! 💯